Africa at the Table: The Urgent Call for Scalable, African-Centric AI Governance

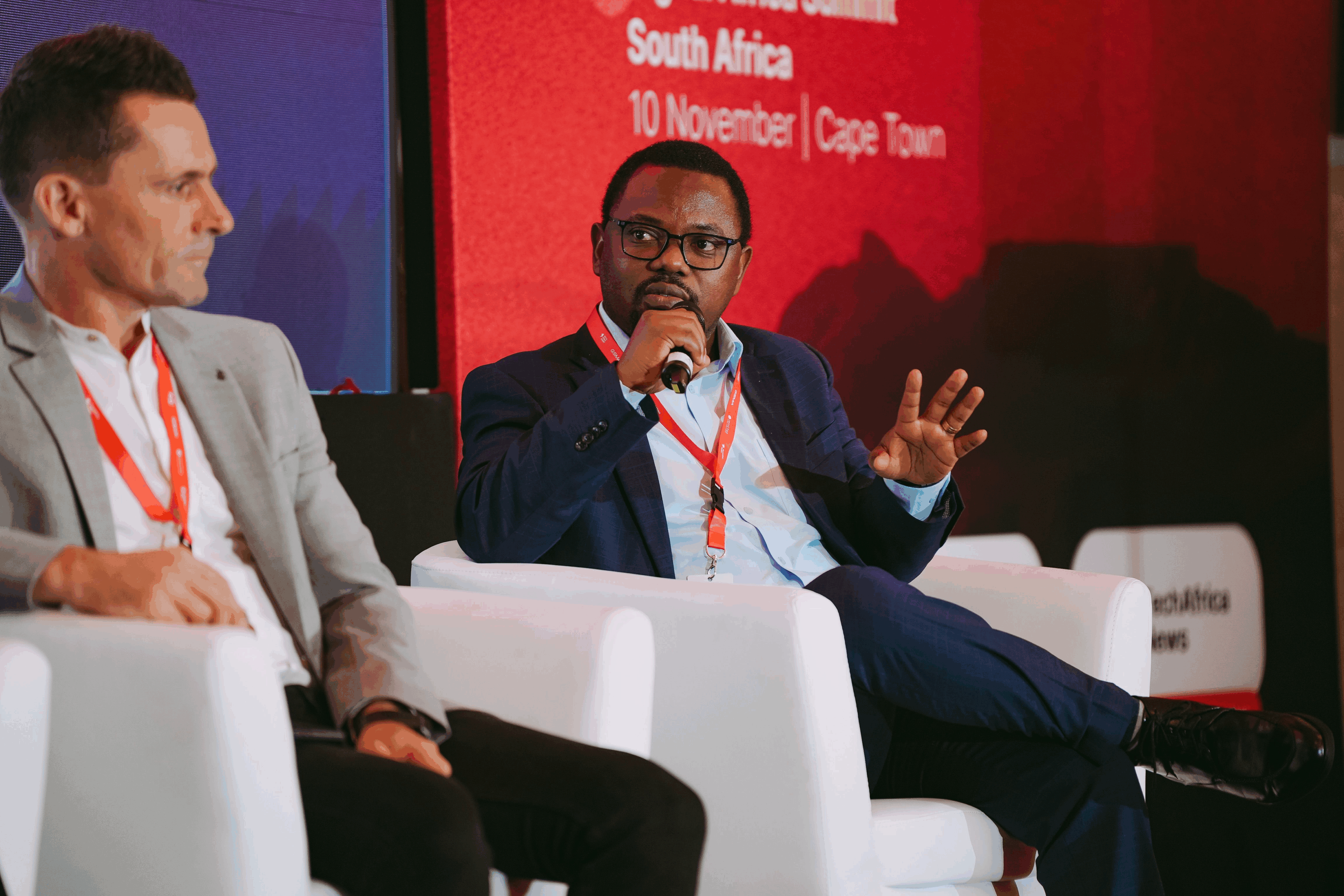

The Digital Africa Summit South Africa 2025 provided a crucial platform for dissecting the often-abstract future of Artificial Intelligence. As the moderator of the session titled “AI for good governance: Data-driven decisions for Africa’s future,” I had the honor of guiding a deeply insightful discussion featuring key voices in African digital transformation: Elizabeth Migwalla, Vice President of International Government Affairs at Qualcomm; Stefan Steffen, Technical Director of Data and AI at Cenfri; and Anthony Mveyange, Director of Program Synergy at APHRC.

It is easy at global conferences to talk in “buzzwords” that lack actionable meaning. But our goal at the Digital Africa Summit in Cape Town was to move past this rhetoric and focus intensely on how we can genuinely use AI to unlock Africa’s potential and identify tangible ways forward. This discussion was not just about the technology itself; it was about the sovereignty, scalability, and societal alignment necessary to ensure that AI serves, rather than subsumes, Africa’s future.

In this #TechTalkThursday article, we look at the key insights from this summit’s discussion, exploring how African leaders and innovators are shaping AI strategies that prioritize local data, ethical frameworks, and inclusive growth.

Navigating the Ecosystem: Scale, Sovereignty, and Solutions

The session began with a challenging question for Anthony Mveyange on the strongest opportunities for AI to improve the public sector and decision-making processes. Anthony wasted no time defining the parameters of successful implementation, stressing the need to integrate African data to help the continent leapfrog challenges in health, agriculture, and education. He highlighted the critical importance of African languages, arguing that innovation is fundamentally “born out of languages”. If AI is externally driven, we must actively work to make it African-centric. This means tailoring campaigns, particularly in global health, so that AI can speak in vernacular languages; whether it is Swahili, Zulu, or Sotini—to penetrate to where it matters most, making services understandable even to children.

This immediate focus on local context naturally led to the challenge of scale. Stefan Steffen, drawing on CENFRI’s extensive experience across various African markets, confirmed that one of the most common pitfalls governments face is designing for data but failing to design for scale. He noted the fragmented nature of AI development, citing that conversations about AI advisory services in agriculture, for instance, are happening independently in Rwanda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Ghana, but they are “not a shared conversation”. The solution, Stefan argued, is developing reusable assets, such as the technology offered by a Ugandan startup able to deliver small language models offline on affordable smartphones, which could be combined with other language models developed across the continent.

To achieve this scale, strong public and private partnerships are paramount. Elizabeth Migwalla positioned Qualcomm as an ecosystem enabler, emphasizing that African innovators must be creating solutions that reflect our national and regional requirements. She shared powerful evidence from Qualcomm’s work, which has successfully put edge AI technology in the hands of young African innovators who are training their systems and developing solutions—like robots for crop monitoring—to solve African problems.

“It takes the intelligent young youth, we have 60% of our population, it takes technologists like ourselves and others, but it also takes our policymakers, regulators, the entrepreneurs and technologists. It’s that kind of partnership that will convert those usage gaps.”.

However, scaling pilots into institutional adoption requires deep governmental collaboration. Anthony Mveyange stressed that this collaboration must transcend national borders, especially since challenges like health crises are transboundary in nature. He pointedly referenced the struggle East African countries had sharing data during COVID. The core issue, he observed, is the fragmentation driven by “sovereignty and national-centric views,” which prevents the replication of small, successful projects. We must foster a unified “sense of belonging” that says, “we are Africans,” leveraging our diversity and heterogeneity as an asset.

I pressed Anthony on whether Africa’s 2,000 languages were, in fact, a barrier. His response was emphatic and crucial: “Our diversity is not a curse, it’s an asset”. He acknowledged the existence of dominant native languages (Swahili, Fulani, Hausa, Zulu) that can be modeled for AI platforms. The barrier is not the languages themselves, but the mindset: “We have been brainwashed to think that English is the only language… Speaking English is not necessarily superiority in terms of innovation”.

“It is possible that the challenge lies in our mindset. Many of us have been conditioned to believe that English is the only language for communication, but that is not true. Speaking English does not equate to superiority in innovation. What we need is a shift in perspective. Take Swahili, for example—spoken by over 400 million people across Africa. I conduct many interviews in Swahili, and it is rapidly expanding across southern Africa, with more countries adopting it. We can start with languages already spoken by the majority, then scale from there. Our diversity is not a curse; it is an asset. The question is how we can leverage it effectively.”

– Anthony Mveyange, Director of Program Synergy, APHRC

Transparency, Literacy, and the Global Table

As we discussed implementation, the issue of public trust came to the fore. Since AI algorithms can feel abstract to the ordinary citizen, I asked Stefan how we ensure transparency and accountability. His answer was beautifully tangible. He suggested that AI models used in public service delivery should operate like traceability systems in agriculture, providing a “QR code” that citizens can scan. This code would allow citizens to understand the model’s source of origin, the data being used, and crucially, how they can seek redress if a decision based on the AI is wrong. Transparency, he concluded, must be designed in from the outset of pilot projects.

This transparency requires citizen literacy. Stefan confirmed that specific AI education is absolutely essential, echoing the importance of digital and data literacy. He shared a compelling example of CENFRI’s ongoing work training Parliament in Rwanda to ensure policymakers can “lead from the front” in understanding the critical AI decisions countries must make.

“I think there has been significant progress in digital literacy and data literacy, and understanding AI is equally important. I also believe that when AI works well, we often do not recognize it as AI. Take Google Maps, for example—it is one of the most sophisticated AI technologies in the world, yet we use it daily without thinking of it as AI. The key is that, when AI is applied appropriately, digital literacy allows us to engage with and benefit from it effectively.”

– Stefan Steffen, Technical Director of Data and AI, Cenfri

Finally, I asked Elizabeth about the risk of AI widening the digital divide. She outlined the policy and investment necessities: infrastructure (like 5G connectivity) and computing capacity (both cloud and on-device/edge AI) are fundamental. Policy frameworks, she urged, must look at global standards but absolutely reflect local realities. Most critically, she stressed the necessity of fostering a local innovation ecosystem—we must build our own tools and systems.

“What is AI? If I ask this question here, how many different answers would I get? The question is not only what AI is, but also what AI can do for you. At its core, AI is an enabler—it helps you do what you are already doing, only better. For example, if you sell vegetables, AI can help you run your trade more efficiently. Regarding your question on how to prevent AI from widening existing divides, several strategies come to mind. Your question is how we can ensure AI does not create a wider divide. Several things come to mind. First and foremost is infrastructure. If people are not connected, they cannot access AI, no matter how advanced on-device AI technologies may be. Therefore, a fundamental policy priority is to ensure widespread connectivity, whether through 5G or other means, to enable equitable access to AI.”

-Elizabeth Migwalla, Vice President of International Government Affairs, Qualcomm

This led to the most powerful insight of our entire discussion, addressing Africa’s place in the global AI discourse:

“If we are not at the table creating the directions, then we are on the menu.”

This statement encapsulates the urgent geopolitical dimension of AI adoption, demanding that Africa dictates how this technology evolves and mobilize sustainable financing to allow innovators to scale. Elizabeth highlighted the staggering difference in funding, noting that the money developed countries are pouring into AI sometimes exceeds our own GDPs.

In wrapping up, I asked the panelists to prioritize sectors for immediate AI intervention. Anthony Mveyange, drawing on a recent survey of policymakers in South Africa, placed Health and Education at the top, emphasizing education for “epistemological transformation”. Stefan Steffen prioritized the MSME segment, recognizing its role as the engine for job creation and growth. Elizabeth Migwalla added Agriculture, acknowledging its fundamental importance: “If you can’t eat, if you can’t produce food”.

Conclusion: A Unified Future

The session confirmed that the conversation around AI in Africa has matured far beyond theoretical potential. We are now grappling with practical necessities: establishing unified, transboundary data ecosystems; developing reusable, scalable assets; and ensuring accountability through radical transparency, perhaps utilizing a “QR code” approach for algorithms.

The overriding takeaway, and my personal reflection as the moderator, is the urgent need for a unified African identity in AI governance and innovation. The challenge is not technological; it is one of will, policy, and integration. We must internalize Anthony Mveyange’s assertion that our diversity is an asset, and apply Elizabeth Migwalla’s call to action: Africa cannot afford to be passive recipients of globally imported frameworks. We must be at the table, designing for our unique languages, our local realities, and scaling our own solutions through deliberate partnerships and essential investments.

If we collectively foster local innovation, invest in AI literacy for citizens and parliamentarians, and demand policy frameworks that are African-centric, we can ensure that AI becomes the equalizer we hope it to be—not widening the divide, but fulfilling the promise of data-driven governance for the continent’s future. The pathway to AI for good is paved not just with code, but with continental cooperation and sovereign intent.